Up Against the Wall: A Brief History of Protest Art

“Of the 51 fortified boundaries built between countries since the end of World War II”, Uri Friedman writes in his article ‘A World of Walls’, “around half were constructed between 2000 and 2014.” This is an astonishing fact, not only because of the increasing rate at which walls are being constructed, but because ‘a world of walls’ is often consigned to the distant past.

The walls that fill our imagined accounts of the besieged city of Troy, the Great Wall of China, Hadrian’s Wall, and the Walls of Babylon, are structures that verge on the mythical - so much so that we forget they were real, tangible barriers. Ancient walls were constructed out of a need for security. They protected their inhabitants, and led societies to move away from a reliance on rituals of sacrifice and desensitization. The emergence of these walled cities, argues the historian David Frye, was the biggest factor in the development of civilization. It is significant then that current movements to improve society - in Lebanon, Iraq, Hong Kong, and Chile to name just a few - regularly feature walls.

In their quest for security, modern protesters have returned to walls, using them as a site of protest. And what better battleground? They occupy public space, providing a canvas with which to assert the individual’s message whilst encouraging a collective response. By its very nature protest art operates at the grassroots level. It is spontaneous, cost-effective and accessible; all criteria that walls fulfill, not least in protest art’s move from our street walls to our social media walls, and back again.

In the post-WWII period that Friedman describes, one of the most famous structures was the Berlin Wall. This week, thirty years ago, this symbol of division between East and West began to disintegrate. The Berlin Wall is now billed as ‘the world’s largest open air gallery’ with murals by 105 artists painted onto its concrete slabs - famous examples include Keith Haring’s now lost 1986 mural, Kani Alavi’s ‘Es Geschah im November’ (1990) and Dmitri Vrubel’s ‘My God, Help Me to Survive This Deadly Love’, commonly known as ‘Fraternal Kiss’ (1990). As anniversary celebrations of the reunification of Germany take place this week, we look to the wider history of wall based protest art that the Berlin Wall has taken up a place within.

Paris, May 1968

The walls of Paris were daubed with slogans over the course of the summer in 1968: “TAKE YOUR DESIRES FOR REALITY,” “NEVER WORK,” “BOREDOM IS COUNTER-REVOLUTIONARY,” “IF YOU RUN INTO A COP, SMASH HIS FACE IN.”

May ‘68 was one of the most important strikes, bringing together students and workers in a rejection of the new model of consumerist living. Barricades were erected in the streets of Paris for the first time since the Paris Comune. The members of the Situationist International (SI) made their own defensive walls, covering the Latin Quarter with their graffiti.

Although aphoristic to contemporary audiences, their ideology was revolutionary. These political slogans were transformed into art, preserved in the documentary photography and La Nouvelle Vague films of the time.

Image: ‘Never work’: graffiti on the walls of Nanterre University, March 1968.

Belfast Peace Lines

In the 2010s there were still 99 barriers across Belfast which prevented freedom of movement across the city. Although starting with The Troubles, a third of these walls had been erected since the Good Friday Agreement.

Irish Republicans began painting the walls of houses in predominantly working class areas in the late 1970s. Artists such as Danny D and Marty Lyons produced murals to unify the Republican cause with images representing armed IRA Volunteers and historic events like the Hunger Strike. The Unionists responded with murals that demarcated territory and signaled loyalty to the UK.

The painted walls are now a major feature of the city, with the longest of the peace lines, Cupar Way, its own attraction. They are also now a symbol of peace, rather than division, with artists from different sides such as Danny D and Mark Irvine (son of the Progressive Unionist Party leader David Irvin) now collaboratively producing murals.

Image: Danny Davenny, Bobby Sands mural on the side wall of Sinn Féin's Falls Road office.

US-Mexico Border

From an initial 14 mile long stretch approved by President Bush in 1990, the US-Mexico border ‘wall’ has grown to 1,954 miles of discontinuous barriers both physical (fences) and virtual (surveillance equipment). President Trump’s controversial expansion of the wall disadvantages migrants, indigenous peoples and local flora and fauna. Recent attention has focused on Trump’s deployment of military personnel to paint parts of the wall in the California town of Calexico, for the primary purpose of improving "the aesthetic appearance of the wall.

Performance artist Ana Teresa Fernandez has repeatedly painted the Tijuana stretch of the border blue so that it blends into the surrounding sky. Her participatory ‘social sculpture’ uses volunteers from communities on both sides of the wall as they spend around six hours painting and ‘making the border disappear.’

Most recently, neon pink see-saws appeared at the border, or more specifically in the border. The result of a partnership between professors Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello and Colectivo Chopeke, these short lived installations brought children together through play. The wall became “a literal fulcrum” where either side’s inhabitants depended on one another.

Image: Ana Teresa Fernandez, ‘Borrando la Frontera’, (2015). Credit: Nick Oza.

Israeli West Bank Barrier

Around 85% of the wall, declared illegal by the International Court of Justice a decade ago, sits within Palestinian territory. It is a site of protest for Palestinians separated from their families and lands, but has become known for its use as a canvas by international artists, despite the many Palestinian murals on the surface.

Banksy has worked on and off at the site since 2003. Standing five metres from the barrier, his ‘Walled Off Hotel’ (2017- present) work is perhaps the most famous. It claims to be the hotel “with the worst view in the world” and has been inundated with visitors.

Palestinian artists have responded to the commodification of the wall as a tourist destination, and accused Banksy of ‘conflict fetishisation.’ Banksy’s satirical ‘street party’ to celebrate the anniversary of the Balfour Declaration was crashed by local artists. The street artist Issa has even defaced his own graffiti, adding “Welcome to the shopping mall" to his pieces in light of tourist souvenirs of the wall.

Whilst painting the mural ‘Unwelcome Intervention’ a Palestinian man reportedly told Banksy ‘"You paint the wall, you make it look beautiful," to which Banksy replied, "Thanks." The Palestinian man then said, "We don't want it to be beautiful, we hate this wall, go home."

Image: Banksy’s ‘Unwelcome Intervention’ (2005)

Arab Spring

Prior to the 2010s, you would have been hard pressed to find graffiti laden streets in the Arab world. Modern graffiti as we know it developed in New York City’s five boroughs in the 1970s, and soon urban metropolises all over were covered in the scene’s tags, bombs and throw-ups.

Following the Arab Spring protests, graffiti quickly became one of the few means of spreading a public message. Of the many that picked up spray cans during this time, a number launched their careers as international artists. These included eL Seed, a French-Tunisian street artist whose style he calls ‘calligraffiti’, Egyptian street artist Aya Tarek and the Franco-Algerian artist Zoo Project.

Image: eL Seed’s mural in Manshiyat Naser.

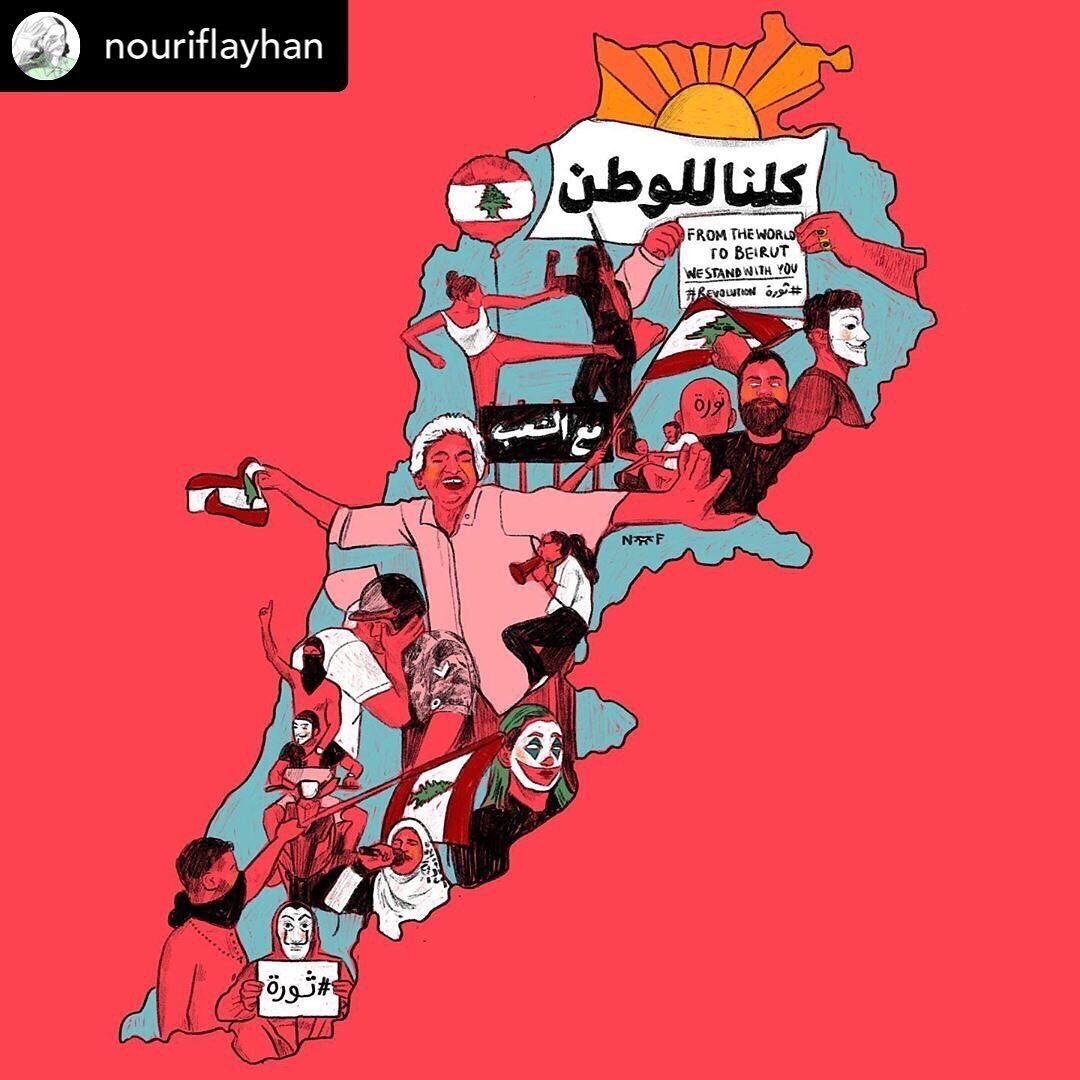

Lebanon’s October Protest

Amidst a zeitgeist of popular uprisings that have erupted in Iraq, Chile, Ecuador, Venezuela, and Hong Kong, Lebanon’s has stood out in particular for the artistic uprising it has catalysed.

Twenty leading arts organisations in Lebanon have issued a statement of solidarity with the protestors, and artists have co-ordinated their own responses - such as Gregory Buchakjian who along with others quickly established ‘Atelier insurrectionnels’ (Insurgency Workshops) to respond to the events on the streets.

Protest art has made its mark on the walls of Beirut, but it has also marked a move to social media walls. Curated by Paola Mounla, ‘Art of Thawra’ is an Instagram page that started a few days after the Lebanese took to the streets. It “is not a mere feed of artworks; it has become the home of Lebanese creatives who wish to paint a different picture for Lebanon.” To date ‘Art of Thawra’ has shared over a 1,000 works of art, reaching 11,000 followers. Spontaneous, accessible and occupying public space, this collection of images shares the qualities of other walls that have been co-opted for protest art throughout history. Crucially, however, it leaves behind the wall’s site-specific context to be truly global.

Words: Ruby Gilding